91st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

91st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

| This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 47thPennVols(talk | contribs) at 17:15, 30 July 2018 (Decreased state flag image size to improve page view). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision. |

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| 91st Pennsylvania Infantry | |

|---|---|

State flag of Pennsylvania, c. 1863 | |

| Active | December 4, 1861 – July 10, 1865 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Engagements | American Civil War

|

The 91st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was a Union infantry regiment which fought in multiple key engagements of the American Civil War, including the Battle of Fredericksburg, Battle of Chancellorsville and Battle of Gettysburg.[1] Following this organization's muster-in during early December 1861, its leaders were presented the regiment's First State Color on December 6. It was manufactured by Horstmann Brothers and Company.[2]

The men who enrolled with the 91st Pennsylvania wore modified Zouave uniforms (dark blue Zouave-style jacket and vest with yellow trim, sky blue sash, sky blue pantaloons, and red fez with blue tassel).[3]

Contents

1 History

1.1 January through November 1862

1.2 Battle of Fredericksburg

1.3 The Mud March and its aftermath

1.4 Battle of Chancellorsville

1.5 Battle of Gettysburg

1.6 Reenlistment and veterans' furlough

1.7 1864 campaigns

1.8 1865 campaigns and war's end

2 Casualties

3 Monuments and memorials

4 References

5 Gallery

6 External resources

7 See also

History

91st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Camp Northumberland, Virginia, 1861 (Matthew Brady, Metropolitan Museum of Art).

The regiment was raised near Philadelphia during the fall of 1861 and mustered into Federal service on December 4 of that year with basic training provided at Camp Chase, Gray's Ferry in Schuylkill County. Field and staff officers included: Edgar I. Gregory (colonel), Edward E. Wallace (lieutenant colonel), Isaac D. Knight, M.D. (surgeon), and George W. Todd (major).[4] The captains of each company were:[5][6]

- Company A: Frank B. Gilbert (resigned January 18, 1863), Francis H. Gregory (promoted from 1st lieutenant the same day; mustered out October 13, 1864), John L. Bell (transferred from 118th Pennsylvania Infantry);

- Company B: Alpheus H. Bowman (mustered out September 10, 1862), Morris Kayser (commissioned but not mustered during promotion from 1st lieutenant, September 24, 1863; resigned, February 16, 1864), J. C. Partenheimer (promoted from commissary sergeant, January 4, 1865);

- Company C: Peter Keyser (resigned, August 15, 1862), James E. Sulger (promoted from 1st lieutenant, August 15, 1862; discharged on surgeon's certificate, October 18, 1862), Theodore H. Parsons (promoted from 2nd lieutenant, October 27, 1862; died from Chancellorsville battle wounds, June 26, 1863), Joseph Gilbert (promoted from sergeant-major, February 24, 1865);

- Company D: Joseph H. Sinex (promoted to lieutenant colonel of the regiment, January 11, 1863), William H. Carpenter (promoted from 1st lieutenant, Co. K, August 11, 1864);

- Company E: John D. Lentz (promoted to major of the regiment, December 20, 1862), Matthew Hall (promoted from 1st lieutenant, December 20, 1862; mustered out, September 9, 1864), Theodore A. Hope (promoted from 1st lieutenant October 31, 1864);

- Company F: Albert C. Fetters (resigned, August 1, 1862), John H. Weeks (promoted, August 5, 1862; discharged on a surgeon's certificate, April 26, 1863), Henry Francis (promoted from 1st lieutenant, May 10, 1864; discharged September 22, 1864), William E. Michael (promoted from 2nd lieutenant, October 31, 1864);

- Company G: Eli G. Sellers (promoted to lieutenant colonel of the regiment, October 31, 1864), William Spangler, James H. Closson (promoted to captain, Co. H, March 1, 1864);

- Company H: Charles S. Brown (resigned, February 22, 1862), Charles Henry (promoted from 2nd lieutenant, May 12, 1862; resigned, April 27, 1863), James H. Closson (promoted from 1st lieutenant, Co. G; died November 23, 1864), George P. Finney (promoted to captain, January 4, 1865);

- Company I: John P. Carie (discharged on surgeon's certificate, February 10, 1863), John S. Donnell (promoted from 2nd lieutenant, October 18, 1864);

- Company K: John F. Casner (promoted to major of the regiment, April 3, 1865), George G. Coster (promoted to captain, May 17, 1865).

January through November 1862

Ordered to Washington, D.C. on January 21, 1862, the regiment made camp three miles outside of the city along Bladensburg Road.[7]

Beginning on February 28, 1862, Company A was assigned to guard duty at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C. with Company E assigned to patrol duties in the city. On March 19, Company D was assigned to duties at the central guard house, and Company G was moved to Long Bridge for duties there while the remainder of the regiment continued to reside at the regiment's barracks at Franklin Square.[8][9]

Less than two months into these new duty assignments, an incident occurred which made newspaper headlines. According to The Evening Star, while Ambrose Baker of C Company was on guard duty at the Old Capitol Prison during the morning of April 21, he shot Jesse B. Wharton, a political prisoner, because Wharton was looking out of a window on the prison's south side at him while he [Baker] was embroiled in an argument with another guard. Struck in the head by a ball from Baker's gun at roughly 11 a.m, Wharton died around 3 p.m. Despite claims that he had been ordered by his superior officer, Lt. Milligan, to shoot any prisoners looking out of windows, Baker was arrested.[10]

Six days later, the regiment was ordered to Alexandria, Virginia, where it relieved the 88th Pennsylvania and was assigned to provost (military police) duty with Col. Gregory and Capt. Joseph H. Sinex appointed, respectively, as military governor and provost marshal of the city.[11][12] Gregory was headquartered "at Mr. C. A. Baldwin's, on St. Asaph street," according to the Alexandria Gazette.[13]

Relieved by the 94th New York on August 21, the 91st Pennsylvania was attached next to the

U.S. Army's 5th Corps, 1st Brigade, 2nd Division which had been ordered to join Gen. John Pope's forces. Stationed near Cloud's Mills, Virginia until August 28, the 91st Pennsylvania then served as an escort for eighty-seven wagons being moved to the Fairfax Court House, but was ordered back to camp upon reaching Annandale. Stationed at Fort Ellsworth from August 29–30, the 91st made camp at Fort Stevenson from September 1–12, when it moved on.[14][15]

Next engaged in duties on the Monocacy Creek as part the Union's Maryland Campaign beginning September 15, the 91st Pennsylvania moved to Antietam three days later.[16][17]

Connecting with the Third Division on October 16, the 91st crossed the Potomac River on a valley reconnoissance mission, during which it skirmished with Confederate troops at Shepherdstown. On October 30, the regiment was moved to Warrenton as part of the Union Army's reorganization during the leadership transition from generals McClellan to Burnside. Encamped at Stoneman's Switch from mid-November to December 11, the 91st Pennsylvania then marched to the Phillips House as part of the lead-up to the Battle of Fredericksburg.[18][19]

Battle of Fredericksburg

The Army of the Potomac crossing the Rappahannock on the morning of December 13, 1862 prior to the Battle of Fredericksburg (Kurz & Allison, U.S. Library of Congress).

Crossing the Rappahanock River at 9 o'clock on the morning of December 13, the 91st Pennsylvanians were ordered to support the 2nd Corps. In response, regimental leaders marched their men through Fredericksburg, and stationed them behind the stone walls of a cemetery outside of the city, a post they held under ordered onto the Union's Fredericksburg Road line, where they were subject to heavy artillery fire and sustained several casualties, including the combat deaths of Lt. George Murphy and Maj. Todd.[20] Todd sustained his mortal wound "when a shot tore off his right leg," according to historian Francis Augustin O'Reilly.[21] The Alexandria Gazette reported that Col. Gregory of the 91st had also been shot in the hand during the battle.[22]

During a charge on Confederate lines begun at 5 o'clock that evening, the 91st then lost an additional two officers and 87 men.[23][24]

Ordered to retreat at 8 p.m., the 91st Pennsylvania marched back into Fredericksburg. Four hours later, it was ordered back out to the front, where it assisted in transferring wounded men from where they had fallen to the care of Union medical personnel, working until sunrise. On December 15, the regiment engaged in the construction of earthenworks, and was also ordered to protect the Richmond Railroad on picket duty.[25][26]

The Mud March and its aftermath

Beginning January 20, 1863, the 91st Pennsylvania joined Gen. Ambrose Burnside's Mud March for which it helped build corduroy roads to facilitate troop and equipment movements. When Union lines bogged down and were unable to progress successfully, the regiment then returned to camp. The regiment was now under the command of Joseph H. Sinex, who had been placed in charge following the resignation of Lt. Col. Wallace.[27][28]

At the end of February, the Alexandria Gazette noted that the regiment had presented its commanding officer, Col. E. M. Gregory, "with an elegant sword, and a splendid horse, in token "of their approbation of his gallant conduct at the battle of Fredericksburg, Dec. 13th.'" The newspaper also noted that the regiment was part of Humphrey's Division at this time, and was encamped at Falmouth.[29]

The regiment was divided beginning April 13 when its left wing was ordered to Banks' Ford and its right to United States Ford, and assigned to picket duty until relieved on April 25 by the 155th Pennsylvania.[30][31]

Battle of Chancellorsville

Three days later, on May 28, the 91st Pennsylvanians joined other Union troops from the 5th, 11th and 12th Corps in a march toward Chancellor House. Crossing Kelly's and Ely's Fords, they reached their destination during the morning of May 1, 1863. At noon, they were ordered to march again for Banks' Ford but, while en route, were redirected to Richardson's Ford, where they joined the line of battle at the right and began digging entrenchments and building earthenworks until relieved of this duty at 6 p.m. on May 3 by soldiers from the 11th Corps.[32][33]

Ordered back to Chancellor House, the 91st Pennsylvanians advanced into a tangled, wooded area, where they skirmished briefly with Confederate troops before moving on. As they approached the CSA's main force, they fell under withering fire, but held their ground until noon when they were forced to withdraw by their severely depleted ammunition supplies. Leaving dead and wounded men behind, they were assaulted by intense artillery fire during their retreat, but were able to regroup and be reposted at the fork of the Chancellorsville and United States Ford roads, where they remained until noon the next day (May 4) when they were ordered to move to the rear of the Union's lines and resume work on fortifications. Ordered back to the front that evening, they protected other retreating soldiers before being ordered to return to camp.[34][35]

Among the casualties incurred during this engagement were Capt. Theodore H. Parsons and Lt. George Black (mortally wounded) and Col. Gregory (leg wound).[36][37]

Relieving the 32nd Massachusetts at Stoneman's Switch on May 28, the 91st Pennsylvanians guarded the railroad from the station to Potomac Bridge before being assigned to cavalry relief on June 4 at United States Ford. Five days later, they were ordered back to Mount Holly Church and then to Catlett's Station before being attached to the forces of Gen. Stephen H. Weed. Ordered to head for Frederick City by way of Manassas Junction, Gum Spring and Aldie, they crossed the Potomac at Edwards' Ferry, they then continued on to Hanover, Pennsylvania, arriving during the evening of July 1, 1863.[38][39]

Battle of Gettysburg

91st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry monument, Gettysburg National Military Park.

At 8 p.m. on July 1, 1863, the 91st Pennsylvanians marched for Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Arriving four hours later, they were ordered to rest on their arms until 4 a.m., when they again resumed their march. Reaching the line of battle, they fought for an hour during an engagement in which E Company's Capt. Hall was severely wounded, and were then shifted to support the left side of the Union's center.[40][41]

At 2 p.m., they marched for Little Round Top to relieve a segment of the beleagured 3rd Corps, and were soon engaging Confederate sharpshooters positioned in the Devil's Den. Gen. Weed was among those killed here during this time. As night fell, the 91st Pennsylvanians prepared for further combat by improving their fortifications.[42][43]

On the Fourth of July, skirmishers from the regiment took several Confederate soldiers prisoner as they infiltrated CSA positions. En route, the 91st sustained 21 casualties (two officers, 19 enlisted men). Departing Little Round Top the next afternoon at 4 p.m., they marched for Marsh Creek, where they remained until ordered to drive CSA troops from Utica, Middletown, Boonsboro, and across the Antietam Creek.[44][45]

As infantry and hospital clerks began to tally the figures for the Battle of Gettysburg, they noted that Pvt. James Ray (Co. E) had sustained a wound to the side of his body.[46]

By July 12, the 91st Pennsylvanians were once again engaged in strengthening Union fortifications. The next day, they fired heavily upon CSA troops nearby, forcing their continued retreat. Advancing toward Williamsport the next day, they captured more CSA soldiers. By campaign's end, they were guarding rail lines along the Rappahannock, as well as the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.[47][48]

Reenlistment and veterans' furlough

Despite the intense combat experiences they had endured during the early part of their service, many of the 91st Pennsylvanians opted to re-enlist when their initial three-year terms of service expired. For a significant number of these men, that reenlistment date was December 26, 1863.[49] Some who did not reenlist were transferred to the 155th Pennsylvania.[50][51]

As a reward for these reenlistments, members of the regiment were granted veteran furloughs and permitted to return home. Departing January 2, 1864, the regiment paraded down Chestnut Street after its arrival in Philadelphia, passing in front of Independence Hall. Regimental headquarters were then opened on Chestnut (below Fifth), and recruiting was resumed under the management of Lt. Shipley.[52] While home on furlough, the regiment's First State Color was retired (in January 1864) and returned to Harrisburg for safekeeping. The regiment was then issued its Second State Color (in February 1864), which was manufactured by the same firm which had produced its first battle flag.[53][54]

Their furloughs over on February 16, the 91st Pennsylvanians reported back to headquarters, and were then moved to the Upland Institute in Chester, where they remained until leaving for winter quarters at Warrenton Junction on March 2.[55][56]

1864 campaigns

During their spring campaign in 1864, the 91st Pennsylvanians departed Culpepper, Virginia at 11 p.m. on May 3, and headed for Germania Ford. Crossing the river early the next morning, they marched on to Wilderness Tavern, where they were ordered to post pickets and make camp. The next morning, they were positioned at the right side of their brigade's battle line near the vicinity of Parker's Store. After one brief charge through a thicket, they remained on duty at their assigned post. Ordered to relieve a unit of reserves from the Keystone State the next day, they skirmished with the enemy off and on until 1 a.m. May 7 when they were ordered to move behind the Union's earthenworks nearby. Fending off a series of enemy charges, they were ordered to withdraw at 9 p.m. During this retreat, Color-Sgt. Robert Chism was trampled by a horse; he died later following the amputation of his injured leg.[57][58]

Assigned to relieve the cavalry stationed near Todd's Tavern around 7 a.m., they slowly advanced under heavy artillery fire to Laurel Hill. Holding this spot for several hours, they then retreated to a ridge at the rear, leaving regimental skirmishers to keep control of the knoll. The bulk of the regiment then set to work bolstering existing earthenworks.[59][60]

During the morning of May 12, the 91st Pennsylvania staged a diversion in the face of heavy rifle and artillery file which enabled the 2nd Corps to effect a larger, surprise charge on the enemy. When Lt. Col. Sinex and Lt. Shipley were wounded during the ruse, Maj. Lentz assumed command. The 91st Pennsylvania then moved on to the Spottsylvania Court House, where it joined with the 140th New York in driving away enemy troops stationed at the Myers' House. Following a brief respite from the action, during which they were relieved by a 6th Corps brigade which ultimately lost the ground they had just gained, they returned with the 140th New York to recapture the area around the court house. After succeeding under heavy artillery fire, they were then relieved again and repositioned in front and to the left of Spottsylvania.[61][62]

Positioned near the front of the Union Army as it marched on Richmond, the 91st Pennsylvania sustained 11 killed and wounded in the fight at North Anna on May 23. F Company Capt. Henry Francis and another four were wounded while serving under heavy fire during the Union's relief of the 4th Division near the Richmond Turnpike.[63][64] Francis had sustained wounds to his shoulder and back, according to The New York Herald.[65]

Transferred to the 1st Brigade, 1st Division under Col. Jacob B. Sweitzer after arriving at Cold Harbor on June 4, they crossed the James River on June 16, and headed for Petersburg. Posted initially to the left of the 9th Corps, they were shifted to the battle lines at the rear of the 3rd Division at dawn two days later. Charging with other Union troops, they drove away the enemy and helped capture a key segment of the Suffolk and Petersburg Railroad. During the intense, four-hour battle, Lts. Edward J. Maguigan and Justus A. Gregory were wounded. As their division moved on at dusk, they drove more CSA troops away by charging a hill nearby. June 21 was then spent on skirmish detail. But these successes were costly. Eighty-two members of the regiment (nearly a full company's worth of men) had been killed or wounded.[66][67]

Assigned to strengthen Union fortifications during most of July and to garrison detail from the end of that month until August 18, the 91st Pennsylvanians briefly engaged the enemy near the Weldon Railroad. By September 30, they were fighting at Peeble's Farm and involved in the capture of a neighboring fort. After building additional fortifications in the area in early October, they drove off the enemy stationed at Davis House, and burned the structure.[68][69]

While involved in the fight at Hatcher's Run on October 28, the regiment sustained additional casualties, including Capts. Casner and Closson, who were seriously wounded.[70][71]

1865 campaigns and war's end

While attempting once again to destroy the Weldon Railroad in early January 1865 and engaging the enemy again at Hatcher's Run on February 6, the 91st Pennsylvania sustained further casualties, including Capt. John Edgar, Jr., who was killed, and Lt. William H. Frailey, who was wounded. In addition, Capt. George P. Finney was captured, as were several other members of the regiment. Then, while fighting at Dabney's Mill and Gravelly Run in late March, the regiment lost 14 more men, including Capt. Hope. During the fighting at Five Forks and Sailor's Creek, the regiment had less costly successes, however, and was able to assist in the capture of supply wagons and CSA troops while driving the larger body of the enemy toward the Appomattox Court House. While there, the 91st Pennsylvanians witnessed the formal surrender on April 9, 1865 of the Confederate Army by Gen. Robert E. Lee.[72][73]

The war technically over but the preservation of America's Union not yet completely assured, the regiment was subsequently marched to Petersburg and Sutherland Station, where it remained until May 4 when it was ordered to Richmond and then Bailey's Crossoads.[74]

On May 23, the 91st Pennsylvania marched in the Union's Grand Review of the Armies in Washington, D.C. It was then finally, officially mustered out on July 10, 1865.[75][76]

Casualties

The 91st Pennsylvania Volunteers incurred at least 200 casualties during its service tenure, including six officers and 110 enlisted men who were killed or mortally wounded in action and two officers and 82 enlisted men who died from disease-related causes.[77]

Under a series of General Orders (No. 302, 307, 319, 320, 365, 368, and 394), issued by the U.S. War Department and Office of the Adjutant General in Washington, D.C. between September 7 and December 12, 1863, the following members of the regiment were declared physically unfit to continue serving, and were transferred to the "Invalid Corps" (Veteran Reserve Corps) from September through December 1863:[78]

- Callahan, John (private, Co. I)

- Detterline, George W. (private, Co. H)

- Dougherty, John (private, Co. F)

- Finley, William (private, Co. F)

- Gordon, James (sergeant, Co. A)

- Hess, Samuel H. (private, Co. F)

- Keeley, Alexander (private, Co. C)

- Lehman, Frederick (private, Co. G)

- Lewis, James (private, Co. A)

- Macauley/Maucaley, David (private, Co. H)

- Maneely, David (private, Co. H)

- McCord, Charles (private, Co. F)

- Parkhill, Joseph (sergeant, Co. D)

- Piers, Frank (sergeant-major)

- Stewart, Samuel (private, Co. E)

- Stott, John (private, Co. G)

- Sweeney/Sweeny, Morris (private, Co. G)

- Wallace, Thomas (private, Co. B)

- Wheelan, Thomas (private, Co. E)

- Wheelan, John (private, Co. E)

- Young, Francis R. (private, Co. A)

Corp. Andrew Brown and Pvt. James Hood of C and H companies, respectively, who had both been wounded near Petersburg, Virginia, died from their wounds on June 19, 1864; both currently rest at the national cemetery in City Point, Virginia.[79] Prior to their exhumation for reburial at the national cemetery, they had been interred on the grounds of the Ruffin Plantation on Prince George Road, roughly a half mile east of Meade Station. Also interred nearby were:[80]

- Bricket, Joseph H. (private, Co. E)

- Keen, Henry (private, Co. D)

- Keys, John (private, Co. H)

- McKee, Willian (private, Co. B)

- Miller, William D. (private, Co. B)

Monuments and memorials

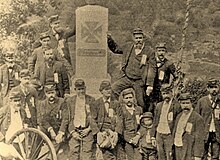

Col. Joseph Synex (center, hand on monument) with former members of the 91st Pennsylvania at the regiment's new monument at the highest point on Little Round Top, Gettysburg National Military Park, c. 1889.

One of the more frequently visited sites at the Gettysburg National Military Park is the castellated granite tower which commemorates the service of the 91st Pennsylvania Volunteers during the Battle of Gettysburg. Erected on September 12, 1889 at the highest point of Little Round Top, "this monument appears to hang over the western edge of the hillside, just off the asphalt path that winds throughout the summit," according to park officials, and documents the exact position defended by the regiment from July 2–3, 1863. Created by the Ryegate Granite Works in Ryegate, Vermont, the monument is composed of a series of five-foot-square blocks topped by a finial emblazoned with the 5th U.S. Army Corps' maltese cross. Situated atop a square base that is seven feet high, the entire structure stands 25.6 feet tall, and is flanked by one-foot-square granite markers with flat tops and mitred edges. (Note: These edges were mitred later as part of a repair effort to fix the damaged corners on the flanking markers.) Polished, inscribed panels convey key details about the regiment's service.[81]

References

^ Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, Vol. III. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1870, pp. 186–233.

^ "91st Infantry", in "Pennsylvania Civil War Battle Flags." Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee, retrieved online June 30, 2018.

^ Lord, Francis A. Uniforms of the Civil War. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., pp. 72–73.

^ Bates, p. 186.

^ Bates, pp.194–233.

^ "Civil War Veterans' Card File, 1861–1866." Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania State Archives.

^ Bates, p. 186.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," in "Pennsylvania in the American Civil War." PA-Roots: Retrieved online July 4, 2018.

^ Bates, p. 186.

^ "Fifty Years Ago in the Star: Prisoner Killed." Washington, D.C.: The Evening Star, April 28, 1912, p. 4.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 186.

^ "Col. Gregory" (provost notice). Alexandria, District of Columbia: Alexandria Gazette, May 13, 1862, p. 2, col. 1.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 186.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 186.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, pp. 186–187.

^ Bates, p. 187.

^ O'Reilly, Francis Augustin. The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, p. 406.

^ "General News." Alexandria, District of Columbia: Alexandria Gazette, December 20, 1862.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 187.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, pp. 187–188.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 188.

^ "War News." Alexandria, District of Columbia: Alexandria Gazette, February 26, 1863, p. 1.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 188.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 188.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, pp. 188–189.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 189.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 189.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 189.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, pp. 189–190.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 190.

^ "Fifth Corps," in "The Casualties: Names of Some of the Killed and Wounded" (Army of the Potomac, Gettysburg). New York, New York: The New York Herald, July 7, 1863, p. 10.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 190.

^ "Civil War Veterans' Card File, 1861–1866." Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 190.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ "91st Infantry," Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee.

^ Bates, p. 190.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 190.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, pp. 190–191.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 191.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 191.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 191.

^ "Operations of the Fifth Corps: Mr. L. A. Hendrick's Dispatch." New York, New York: The New York Herald, June 7, 1864, p. 1.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, pp. 191–192.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 192.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, p. 192.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ Bates, pp. 192–193.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ "Review of the Armies; Propitious Weather and a Splendid Spectacle. Nearly a Hundred Thousand Veterans in the Lines. The Names and Order of the Several Corps and Divisions...." New York, New York: The New York Times, May 24, 1865.

^ "91st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers," PA-Roots.

^ General Orders of the War Department Embracing the Years 1861, 1862 & 1863, Vol. II. New York, New York: Derby & Miller, 1864, pp. 399, 406, 413, 423, 507, 517, 608, 617, 661, 665, 691, and 697.

^ "Brown, Andrew" and "Hood, James," in "Civil War Veterans' Card File, 1861–1866." Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

^ Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers Who Died in Defence of the American Union, Interred in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, Arkansas, Texas, Utah Territory, and on the Pacific Coast. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1867, p. 115.

^ "Gettysburg National Military Park: Little Round Top Cultural Landscape Report, Treatment & ManagementPlan." Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: National Park Service, U.S. Departmnt of the Interior, March 2, 2012, p. 3-18.

Gallery

Capt. Alpheus H. Bowman (shown as ret. Brig. Gen., 1926)

Capt. John P. Carie

Capt. Albert C. Fetter

Pvt. Thomas J. Kurtz

2nd Lt. Theodore H. Parsons

Lt. Col. George W. Todd

External resources

- "91st Infantry" (first and second state colors), in "Pennsylvania Civil War Battle Flags." Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee, retrieved online June 30, 2018.

- "91st Regiment," in "Registers of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861–1865" (Records of the Department of Military and Veterans' Affairs, RG-19). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives, retrieved online July 4, 2018.

- Banks, John. Letter from 91st Pennsylvania Capt. Thedore Parsons detailing the circumstances of C Company Sgt. William Brown's death (includes image of letter and photo of Parsons in uniform), in "A dog, a Pennsylvania soldier and a death at Fredericksburg." John Banks' Civil War Blog, December 10, 2017.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania volunteers, 1861-5 : prepared in compliance with acts of the legislature. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869–1871 (courtesy of the Hathi Trust, University of Michigan).

- Gasbarro, Norman. "91st Pennsylvania Infantry – Pennsylvania Memorial at Gettysburg." PA Historian, retrieved online June 30, 2018.

See also

- List of Pennsylvania Civil War regiments

Categories:

- Pennsylvania Civil War regiments

- 1861 establishments in Pennsylvania

- Military units and formations established in 1861

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1865

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgPageParseReport":{"limitreport":{"cputime":"0.256","walltime":"0.315","ppvisitednodes":{"value":1597,"limit":1000000},"ppgeneratednodes":{"value":0,"limit":1500000},"postexpandincludesize":{"value":7468,"limit":2097152},"templateargumentsize":{"value":1160,"limit":2097152},"expansiondepth":{"value":11,"limit":40},"expensivefunctioncount":{"value":1,"limit":500},"unstrip-depth":{"value":0,"limit":20},"unstrip-size":{"value":35233,"limit":5000000},"entityaccesscount":{"value":0,"limit":400},"timingprofile":["100.00% 209.044 1 -total"," 37.80% 79.026 1 Template:Infobox_military_unit"," 34.00% 71.066 1 Template:Infobox"," 21.56% 45.068 1 Template:Reflist"," 6.19% 12.934 5 Template:WPMILHIST_Infobox_style"," 5.56% 11.621 1 Template:Portal"," 4.06% 8.494 1 Template:Flag"," 3.05% 6.379 1 Template:Country_data_United_States"," 1.91% 4.002 1 Template:Template_other"," 1.41% 2.938 1 Template:Main_other"]},"scribunto":{"limitreport-timeusage":{"value":"0.027","limit":"10.000"},"limitreport-memusage":{"value":1419473,"limit":52428800}},"cachereport":{"origin":"mw1325","timestamp":"20190112045453","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false}}});});{"@context":"https://schema.org","@type":"Article","name":"91st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment","url":"https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/91st_Pennsylvania_Infantry_Regiment","sameAs":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q4645760","mainEntity":"http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q4645760","author":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Contributors to Wikimedia projects"},"publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject","url":"https://www.wikimedia.org/static/images/wmf-hor-googpub.png"}},"datePublished":"2011-04-14T19:29:25Z","dateModified":"2019-01-03T11:10:31Z","image":"https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Pennsylvania_State_Flag_1863_pubdomain.jpg"}(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function(){mw.config.set({"wgBackendResponseTime":493,"wgHostname":"mw1325"});});